Group 3: Sandy Brahaspat, Mallory DelSignore, Domenica Piccoli, Jasmine Vrooman

In completing our group project, we decided to use the online software Kumu to map out prevalent connections between themes like conventional gender roles, appearance and character identity, class, marriage, revenge, and anguish in Wuthering Heights, Great Expectations, Society in America, In Memoriam, and Reuben Sachs. We began our project by assigning different texts to our group members to draw connections between our selected themes, however, we quickly realized that we worked better together than apart. We quickly learned that being able to bounce ideas off each other and draw connections from multiple texts ensured the depth of our content and we were able to gain a wider scope of Victorian literature by making these connecting our themes to our five texts.

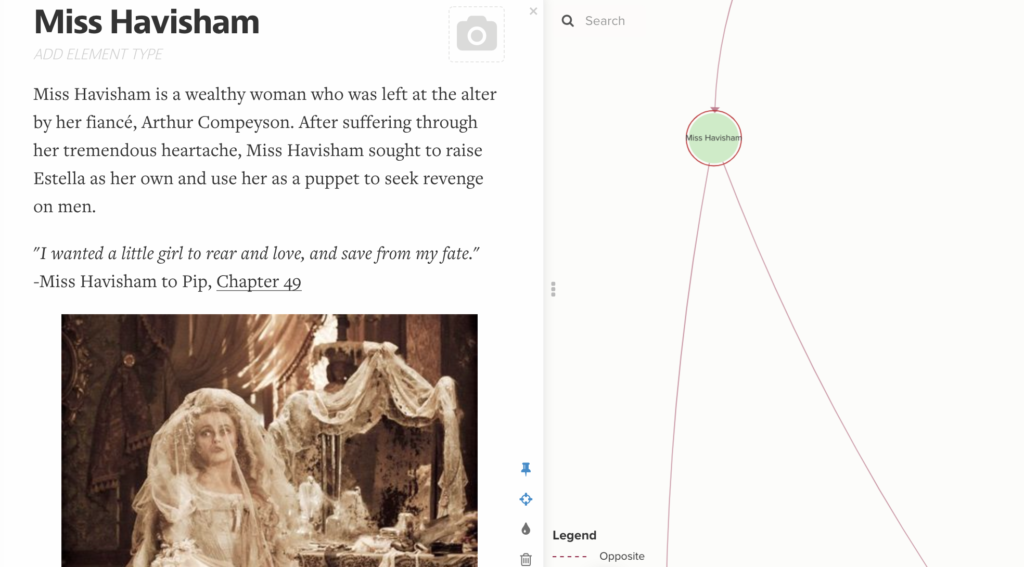

In operating Kumu, you must first add “element bubbles” which categorize a main idea or thought, or in our case, selected texts, characters, or themes. Each “element bubble” can be connected to other “element bubbles” by implementing connection lines. These connection lines operates as a pathway to view the connection visually because it holds the descriptive content that explicitly states the connection with text evidence. After doing this multiple times, our creation ended up looking like “spider web” map. At first, Kumu was a little difficult to navigate as the organization can seem overwhelming when making various connections. However, after playing around with the outline and the accessibility of the program to move bubbles and lines around, we found a way that seemed less overwhelming. For example, we first created individual bubbles for our chosen texts, then with a connecting line from the corresponding texts we added the character bubbles, after that we created the element bubbles for our selected themes and then began drawing connections between characters from the novels to our themes. For example, in our text bubble for Wuthering Heights we made a connection between Heathcliff’s character and the theme of Gender Roles. After addressing this connection, we made the assertion that Heathcliff’s treatment towards Isabella is indicative of the toxic masculine gender roles that he exemplifies throughout the novel.

Despite the power of Kumu, we wish there was a way to directly connect multiple texts to each other as well as the theme; this would make the project a bit more seamless and allow it to be seen from another perspective. In addition, we found it difficult to put the Kumu presentation together because it did not operate like google docs, where all contributors can work at the same time on the same project. In order to view updates or changes to our project, we had to constantly refresh the page which proved to be rather time consuming. Nonetheless, the mapped out project still conveys the connections between themes across our chosen texts very well.

In order to help you effortlessly navigate our project, we have provided a detailed guide with instructions that should clarify any confusions or concerns you may have.

To begin, visit our map at: https://kumu.io/domenicapiccoli/victorian-literature-connections#victorian-literature-connections

Once you have arrived at our page, follow the directions listed below.

Step 1: Click on the bubbles with the images of our selected authors for a brief introduction of their texts. From left to right, you will find Emily Brontë, Harriet Martineau, Charles Dickens, Alfred Tennyson, and Amy Levy. For example, if you hover your cursor over the Charles Dickens bubble, you will find a brief introduction about Great Expectations and an illustration of the soft cover Penguin edition.

Step 2: Click on the bubbles with the character names for a brief introduction about their roles in their respective novels. For example, if you click on Miss Havisham’s character bubble, you will find a brief snapshot of her life and an image from the 2013 film adaption of Great Expectations

Step 3: The orangey-yellow bubbles below the character bubbles indicate the specific themes we narrowed our focus on. From left to right, you will find class, appearance and identity, gender roles, anguish, marriage, and revenge.

Step 4: To isolate a specific theme, hover your cursor over a theme bubble.

Step 5: The lines that connect the characters or texts to specific themes contain our analysis of the connections. Click a line to learn more about how and why we made our connection.

Step 6: Repeat and Enjoy!