Group 1

What exactly is the genre of the novel and how did it begin, rising to such prominence at the start of the 19th century? In The Rise of the Novel, Ian Watt claims that the defining characteristic of the novel is the mode of realism through which it operates and that this, as a result, sets the novel apart from that of other works both of its time and those of the past. The most general definition of the novel is that it is often fictitious in nature, in narrative form, about book length, and represents both the characters and the actions of the story with some degree of realism. If we compare Jane Austen, an author who was considered one of the first true novelists to, say, Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte, who often times gets mistakenly lumped into the same category as the former, we begin to see how and why the novel as a genre branched off into a territory of its own, so to speak. On page 14 Watt says:

“Nevertheless a broad and necessarily summary comparison between the novel and previous literary forms reveals an important difference: Defoe and Richardson are the first great writers in our literature who did not take their plots of mythology, history, legend or previous literature. In this they differ from Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare and Milton, for instance, who like the writers of Greece and Rome, habitually used traditional plots” (Watt, 14).

Here, we see that authors like Defoe, are essentially the forerunners of the novel as a genre, as, he was one of the first of his time to place significance and value on originality and individuality rather than the traditional or typical plots woven throughout the history of most of the early texts in the Western world. Novelists like Defoe used literature in such a way that “most fully reflect[ed] this individualist and innovating reorientation,” as, many previous literary forms were based solely on either past history, myths, and/or religious matters.

Northrop Frye also contributes to the conversation in trying to define what exactly makes a typical novel the “typical novel” and illustrates this through comparing Jane Austen and Wuthering Heights, in an effort to separate the novel from what he calls the “miscellaneous heap of prose works now covered by that term” (Frye, 6). Northrop Frye claims that the “essential difference between the novel and romance lies in the conception of characterization” and that “the romancer does not attempt to create ‘real people’ so much as stylized figures which expand into psychological archetypes” (Frye, 6). Bronte’s Wuthering Heights is a prime example of the typical conventions of the romance genre as opposed to the novel. In contrast, he asserts that the novelist, “deals with personality, with characters wearing their personae or social masks” and that he (or she) “needs the framework of a stable society” (Frye, 6)– much like what we see through the eyes of Esther Summerson, the protagonist in Dickens’ novel, Bleak House. While the stories and characters within the novel may be fictional, most of Dickens’ works fit very well within the conceptual model of the novel as he often creates a fictional approach to history in his works. Unlike others of his time, Dickens invests what Frye refers to as a “chief interest in human character as it manifests itself in society” (Frye, 7) and this, as a result distinguishes literature being written and viewed through this lens and why it was perhaps so infectious in its appeal beginning in the 19th century to modern day. It is also interesting to note that the word novel comes from the word “nuvel” meaning new in French, and that in its beginnings, the novel served as a platform to disseminate information and/or news.

This idea of the novel as “the novel of purpose”, one in which authors would use realism, to allow the audience to relate to the events of the story and apply them to their own lives, is prevalent in chapters 2 and 3 of Amanda Claybaugh’s book, The Novel of Purpose: Literature and Social Reform in the Anglo-American World. Claybaugh focuses on the idea that reformists writings of the 1800s influenced the way authors viewed the purpose of the novel. This book also posed an interesting view of Charles Dickens’ use of the novel. Claybaugh proposes that Dickens did not view/set out to write his work as reformist until the late 1840s. Under this time frame, Oliver Twist, our debut novel that started our journey into Dickens’ universe, wouldn’t have been written to reform: “It was only in the late 1840s, after he had already written five novels, that Dickens began to identify himself publicly as a reformer, and only sometime after that he began to write in a straightforwardly reformist mode himself” (Claybaugh 52). She provides evidence for the claim that “Dickens himself did not understand these scenes [workhouse, debtor’s prison, etc.] to be reformist at the time he wrote them” by citing his prefaces to his early works. Claybaugh states that Dickens’ preface to Oliver Twist merely “defends the propriety of writing about thieves” (52) and doesn’t mention the workhouses or the slums, which modern readers view as the central aspect of reform in the novel. Claybaugh then demonstrates Dickens’ view of himself as a reformist novelist by citing his prefaces to the Cheap Editions of his novels, wherein he urges his audiences to concede that socioeconomic reform is necessary. She claims that Dickens began to view himself as a reformist after he conceived that the publication of Nicholas Nickelby, a story about the terrible conditions in Yorkshire boarding schools, led to the closing of many of these schools. He also took a more definitive role of the reformist after his tour of American schools, prisons, and slums, noting the similarities between the American and English versions of these institutions and becoming determined to change his nation’s socioeconomic atmosphere (54.)

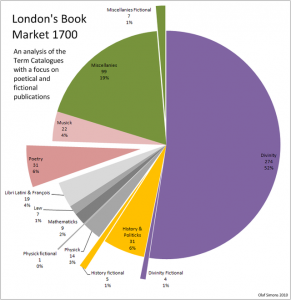

London’s book market 1700, distribution of titles according to Term Catalogue data. The poetical and fictional production does not have a unified place yet.

Sources:

Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Novel

http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=HjXPUv4tOJ0C&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=purpose+of+the+novel&ots=1IoqCB8M2D&sig=bgRVs-b_jcFe71tYMw2SWZLhaQg#v=onepage&q=purpose%20of%20the%20novel&f=false

rise of the novel – http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=PmwfH7X-IKAC&oi=fnd&pg=PA7&dq=%22rise+of+the+novel%22&ots=FVZlTnaNnn&sig=lFMlfizqhwkcxfAq8ihVbr6OGBU#v=onepage&q=%22rise%20of%20the%20novel%22&f=false

Possible discussion questions:

#1. How does Bleak House fulfill its purpose as a novel according to Frye and/or Claybough?

#2. (If the class is alright with going back to Oliver Twist) How does Claybaugh’s theory of Dickens’ purpose for writing present itself in OT and Bleak House? Explain whether or not you believe there are differences in Dickens’ writing that convey Claybaugh’s idea of Dickens’ self-perceived transformation from informer to reformist.

Blog post written by: Elizabeth Messana and Audrey Buechel

Group Members: Jenna Cecchini, Elizabeth Messana, Alexis Donahue, and Audrey Buechel