For our project, we were interested in gaining a better understanding of the role family plays in both Wuthering Heights and Great Expectations. We can also begin to understand what role family plays in Victorian literature in a more general sense by comparing and contrasting these two family systems as samples. We felt that noting similarities between the families was important to help decide which character connections would be most beneficial to our project. For example, Pip and Heathcliff’s histories as orphans who go from rags to riches makes them a compelling duo to focus on. By then showing the differences between the characters’ familial relationships however, we are able to understand what effects these relationships had on their development. Why do two characters who have so much in common in terms of background turn out so differently? This project seeks to answer that question, along with many other questions regarding the family systems within these novels.

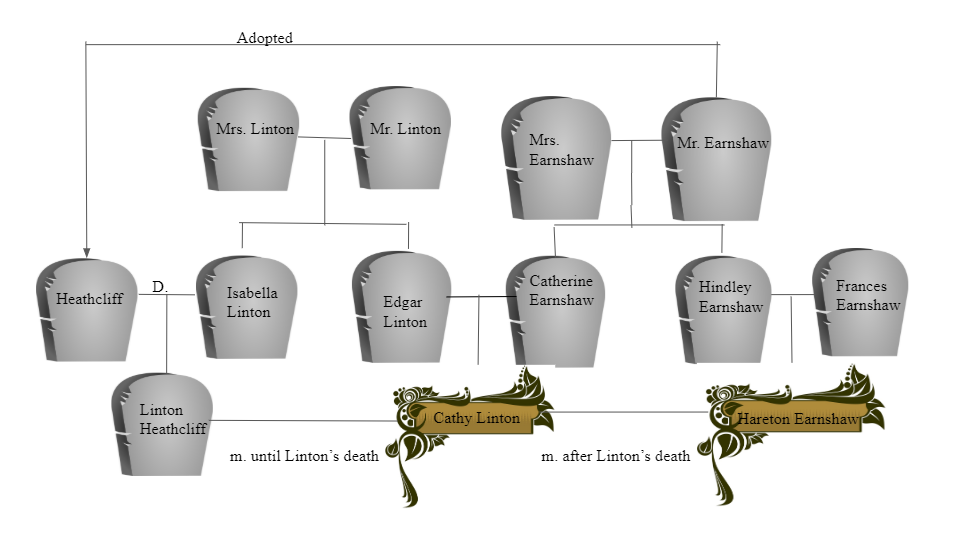

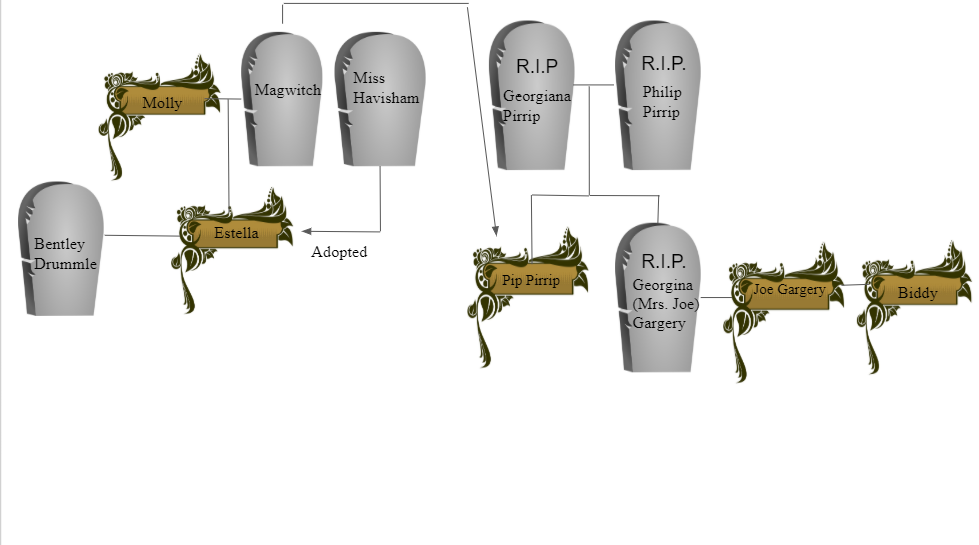

Mapping out a genealogy of the families in Wuthering Heights and Great Expectations allows us to not only demonstrate connections within the families of their respective stories, but also helps to make connections between both of the novels. Many similarities and differences between the families can be deduced simply by looking at the visual layout of the trees, while others can be understood by reading the included bios and relationship descriptions. Focusing on these familial relationships, connections between the novels become visible.

To further expound on the Pip/Heathcliff example, it is worth acknowledging other similarities in their backgrounds. As stated, both of these characters were orphans, and they were each adopted into families where one or more individuals treated them with cruelty: Mrs. Joe for Pip, and Hindley- along with a few others- for Heathcliff. However, Pip and Heathcliff react very differently to their situations, and our project hopes to offer some sort of insight as to why that is. We put an emphasis on many of the important relationships in these novels, and acknowledging these relationships makes questions like this clearer. In this case, although Pip and Heathcliff come from similar backgrounds, it seems that Pip’s relationships with parental type figures such as Joe, and later Magwitch, have an important effect on him. While Pip is an outcast for much of the story, the presence of characters like Joe throughout the entirety of the book give him some sense of family and belonging. Heathcliff however, loses his one truly nurturing parental figure early on in Wuthering Heights. With Mr. Earnshaw’s passing, Heathcliff’s sense of belonging dies as well. Even Catherine’s romantic love is no replacement for familial belonging.

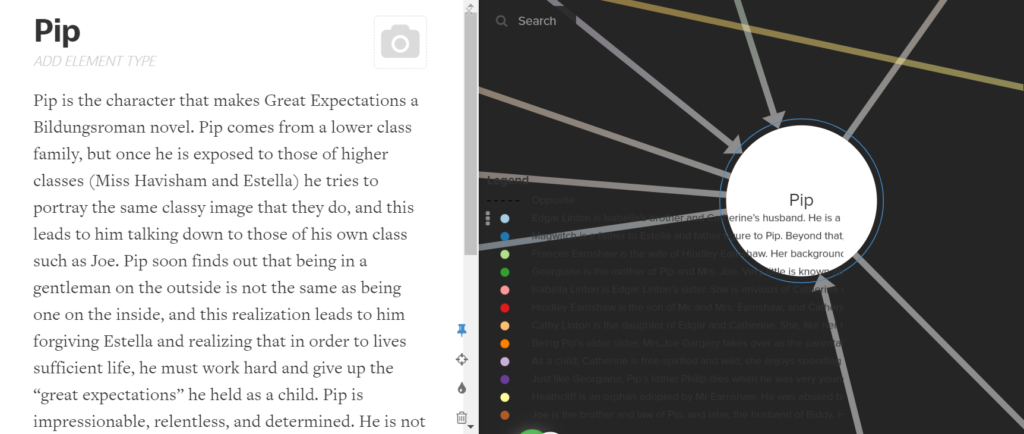

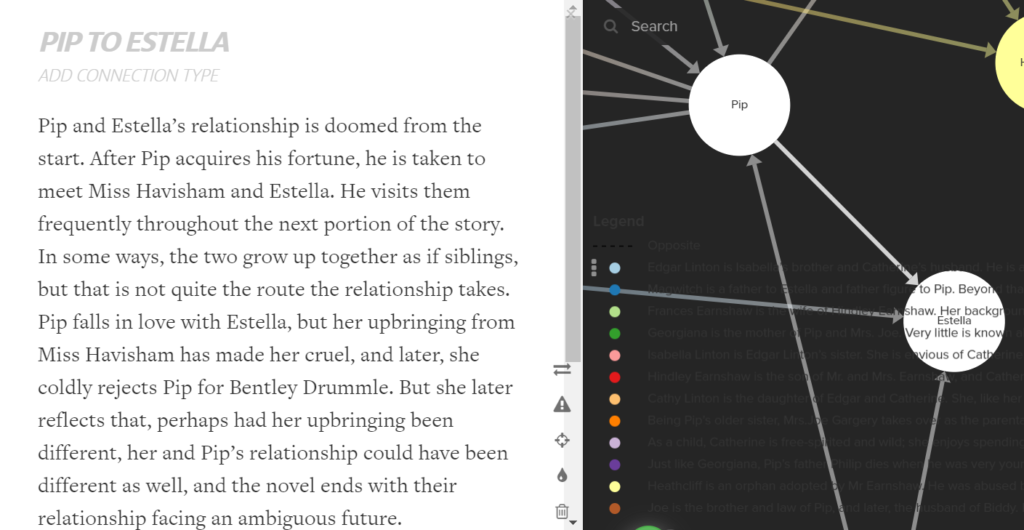

Our Kumu family tree consists of individual characters, represented by different colored circles, and lines of relationship between characters. Clicking on the circles will pull up that character’s bio, which gives a brief overview of his or her history and significance to the story. The various lines branching off of the circles represent their relationships with other characters. Let’s look at Pip for an example of this. When you click on his character circle (IMAGE 1), his bio will pop out from the left (IMAGE 2). Because Pip is the central character of Great Expectations, he has more relationships than the other characters of the story. One of these relationship lines connects him with Estella. Clicking on the line that connects the two will open their relationship description (IMAGES 3&4). This can be done with every character and every relationship within both Wuthering Heights and Great Expectations. This allows viewers to compare and contrast the family systems in each of the novels. We included a few examples of characters and relationships that may be connected between the stories, such as Pip and Heathcliff or Estella and Catherine. Clicking on the lines that link these characters will bring up an explanation of how the characters from the different novels are connected. We also included an example of relationships we felt parallelled each other in the novels: Catherine and Heathcliff’s relationship compared with Pip and Estella’s. However, we feel that the project allows viewers to easily make their own connections between the books, as well as to build an understanding of the functions of these family systems. Something that seemed to emerge from the analysis of both family units is how patterns of abuse are transgenerational. In Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff is abused by his “family,” particularly by Hindley. Heathcliff in turn treats the next generation, Linton and Hareton, with similar cruelty and contempt. Something similar can be seen in Great Expectations. Pip grows up in a household where he witnesses Joe, his father-figure, accepting abuse from Mrs. Joe, Pip’s maternal figure. With this serving as Pip’s primary model of family and love, he goes on to fall in love with Estella, from whom he accepts similar abuse.

After deciding to focus on familial connections in the stories, we began trying to figure out what tool or website would be best to design our family tree(s). We worked off sort of “base models” of the family trees that Ashley created in Google Slides (IMAGES 5&6). This was really important in figuring out which characters needed bios, and which relationships we wanted to focus on. The first program we tested was an online family tree builder called FamilyEcho. The website was interesting, but it presented several challenges such as how we would demonstrate relationships and make them interactive. We also played around with the website designer Wix, where we tried to build a website to display the genealogies and connections. However we decided that this was not an ideal format. Dr. Schacht suggested the website Kumu, and after exploring it, we decided it was perfectly suited to our project. Kumu shows different bubbles which have the names of the characters in both of the novels we are exploring. The lines show the connections that these characters have with each other. When pressing on the line that links two characters together, we can see their relationship to one another or how they might be similar. The entire time we were testing different programs, we used Google Slides as a workplace, where we wrote up the character bios, relationships, and connections. This made it extremely simple to adapt to whatever format we were testing at the time. The end result of all of this is a study in how nurture takes precedence over nature or circumstance.

IMAGE 1

IMAGE 2

IMAGE 3

IMAGE 4

IMAGE 5

IMAGE 6