The overwhelming popularity which greeted Dickens’ Oliver Twist in 1838 may elicit the belief that all readers reacted with similar admiration and enthusiasm; however, in light of the ongoing debate surrounding the New Poor Law, nothing could be farther from the truth. Dickens’ shocking representation of the unbearable conditions in the workhouses became both a means to advocate social reform, and a subject of derision to those who opposed the ascent of the lower class, making Oliver Twist an axis for controversy.

Those reviews which applaud Oliver Twist commend Dickens for his realism and honesty in the novel’s reflection of Victorian society, as well as for his incomparable ability to create consistently lifelike characters. John Forster insists, “…the absolute truth and precision of its delineation are not to be disputed. And truly, where the object of a writer is exact description, the characteristics of humanity…Indeed we wish that all history were written in the spirit of Oliver Twist’s history.” (Norton 399) Forster very decidedly uses the term history in discussing Oliver’s tale, even going so far as to claim, “In his writing we find reality,” to emphasize his belief in the absolute truth of Oliver’s experience. (Norton 400)

The Literary Gazette showers Dickens with praise for his morally motivated exposure of the workhouse conditions, “[Dickens] has dug deep into the human mind; and he has nobly directed his energies to the exposure of evils—the workhouse, the starving school, the factory system, and many other things, at which blessed nature shudder and recoiled.” Astonished and gratified by Dickens’ moral contributions, the Gazette goes on to declare, “As a moralist and reformer of cruel abuses…long may he live to increase our debt of gratitude!”(Norton, 402) Many readers, especially those most familiar with the workhouses and the lives of the poor, shared in this fervent sentiment.

But some are not so easily convinced of Dickens’ honesty, or choose not to be. Richard Ford, perhaps one of Dickens’ most vehement critics, adopts the staunch position that Dickens’ representation of the New Poor Law is grossly exaggerated and even dishonestly concocted in order to stir political action. Ford alleges, “The abuses which he ridicules are not only exaggerated, but in nineteen cases out of twenty do not at all exist.” (Norton 407) He asserts that the workhouses and their proprietors are being attacked by Dickens, “and in our opinion with much unfairness.” Ford uses the phrase “our opinion” because he identifies with the upper class, which is arguably responsible for the abuse of the poor, and therefore more than willing to sweep the issue under the rug entirely. Ford’s rebuttal should be interpreted with the knowledge that his position in society was one of considerable status, being the son of a parliament member and son-in-law to the Earl of Essex; his social position would have made it all too tempting to turn a blind eye towards that least appealing section of the social strata.

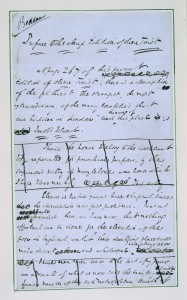

Dickens was not deterred in the slightest by adverse response; in fact, he chose to turn these reactions to his advantage, using them to validate the importance of the tale. In the preface of the 1841 edition of Oliver Twist, Dickens responds to his critics, “I am glad to have it doubted, for in that circumstance I find sufficient assurance that it needed to be told.” (Norton 7) Nearly a decade later, Dickens claimed another opportunity to address his opposition directly. In the preface of the 1850 publication, or “cheap edition” of Oliver Twist, he writes, “Eleven or twelve years have elapsed, since the description was first published. I was as convinced then, as I am now, that nothing effectual can be done for the elevation of the poor in England, until their dwelling places are made decent and wholesome.” (Preface) This edition was released at a lower cost than previous editions in order to reach a wider audience. Dickens clearly wanted Oliver Twist to be read as a testimony of fact, with the intention of encouraging improvements to the living situation of the poor. These responses show that Dickens had a continuing conversation with his audience, whether they be supporters or critics, and viewed any opportunity to address them as invaluable.

The conversation surrounding the rights of the poor expanded during and following the publishing of Oliver Twist as a serial in Bentley’s Miscellany. The mass of loyal readers following Dickens’ writing from the mid 1830’s onward not only created financial security for the author; but also ensured that Dickens’ moral beliefs on the subject of poverty were well known and respected by many for an extended period of time. These same readers in the next few years made up the population which was driving a Victorian political action known as the Chartist Movement. Although it would be nearly impossible to prove a causal link between the publishing of Oliver Twist between 1837 and 1839 and the birth of Chartism in 1838, it is very reasonable to argue that the two are intertwined.

Dickens’ moral beliefs are reflected in the mantra of the Chartists, who in a national protest, fought for suffrage for the common man, as well as equal representation in the House of Commons. The movement began with the publication of “The People’s Charter” in 1838, and continued for roughly twenty years. The charter’s heading included six simple demands for the House of Commons: universal suffrage (for men of course), that no property qualifications would be required to vote, annually elected parliaments, equal representation according to population in each district, payment of the members of parliament (that working men may hold an office), and voting to be conducted by secret ballot in order to eliminate the coercion of voters. (People’s Charter) These goals were intended to give the working and lower classes a voice in the society which seemed so bent on their suppression, an ambition which Dickens no doubt supported.

Despite Dickens’ surging popularity, his commentary and criticism of the New Poor Law drew both praise and derision from his contemporaries, as seen in a number of prominent literary publications such as The Examiner and The Quarterly Review. While Oliver Twist may not have had a tangible, immediate effect on working class living conditions, it provided the impetus for discussion among prominent public figures. Dickens instigated a discussion which would continue for several decades, and eventually lead, however indirectly, to meaningful changes in the everyday lives of the English poor.

Blog Post By: Hannah Glaser

Group Members: Colin Peartree, Michael Stoianoff, Kevin O’Connor, Michael Adams

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles, Fred Kaplan, John Forster, and Richard Ford. Oliver Twist: Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Sources, Early Reviews, Criticism. New York: W.W. Norton, 1993. Print.

Dickens, Charles. “Preface to the ‘Cheap Edition’ of Oliver Twist.” Preface to the ‘Cheap Edition’ of Oliver Twist. British Library Board, n.d. Web. 10 Sept. 2014. http://www.bl.uk/learning/langlit/dickens/campaigning/manuscript/olivertwist.html

“The People’s Charter.” The People’s Charter. British Library Board, n.d. Web. 10 Sept. 2014. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/struggle/chartists1/historicalsources/source4/peoplescharter.html

Discussion Question

What can we say about the moral stance in Oliver Twist based on how the moral situations, decisions, and statements that we see among the characters are presented to the reader?

Group 5

The anonymous review discussed by group two states that Dickens’ characters lack a moral sensibility that readers can relate to or even understand. The reviewer concludes that Dickens does, indeed, paint a grand picture of morality through the character of Nancy, however. Nancy is portrayed generally as a destitute, promiscuous, female criminal who hangs around with the likes of Bill Sikes and Fagin. However, there is a shift in her moral expression when Oliver comes into the company of the thieves. Nancy soon is quick to defend Oliver from the unforgiving schemes of Sikes and Fagin when they begin manipulating him for their personal gain. This new found morality is expressed in a scene between Fagin and Nancy soon after Fagin discovers the news about the failed heist. Fagin’s concerns for Oliver’s whereabouts are attacked by Nancy. She exclaims, “The child is better where he is, than among us; and if no harm comes to Bill from it, I hope he lies dead in the ditch” (Dickens 175). Nancy’s desire for Oliver to be found dead instead of returning to the awful, immoral life that he has found himself in represents the establishment of a moral compass within a character who has up until then lived an immoral life. Dickens in essence is saying that morality can come from even the lowest echelons of society. We see here a moral stance that Dickens is taking as an author through the story of Oliver Twist. He believes that even criminals can have a sense of morality. Those viewed to be immoral are not always objectively immoral in nature. There is always a chance for retribution and this is not seen as clearly anywhere else than through the character of Nancy who is influenced by Oliver’s moral goodness to keep him safe from the clutches of the thieves’ immorality. Even though Oliver may be a cardboard cutout for the moral goodness and Fagin and Sikes never go deeper than being immoral criminal scum we see a very important character presented in the sea of one dimensional characters. This is what Dickens ascertains. Although there are many people in the world who seem to be either good or bad there are people who deal with moral conflict within themselves, who can ultimately come out on the side of morality like Nancy does.

Group 1:

Group five concludes, after analysing morality within Oliver Twist, that morality can come from “even the lowest echelons of society”. We agree with this statement as an overall concept, however we believe that rather than morality suddenly appearing as the result of a single incident, it develops and grows over time as an individual develops. For example, from what we know of Nancy as a character, to us, she seems to have led an immoral life as group five points out: “Nancy is portrayed generally as a destitute, promiscuous, female criminal who hangs around with the likes of Bill Sikes and Fagin”. However, placed within her own personal history (which we know only a little bit about), Nancy’s moral compass, while not compatible with ours, exists. Rather than her mysteriously developing a moral compass out of nowhere when Oliver steps into her life, it appears more likely that this is just the first time we notice it as an audience because it has finally aligned with something we can recognize as ‘good’.

In his preface to Oliver Twist, Dickens himself states that Oliver’s behavior is his attempt as a writer to show “the principle of Good surviving through every adverse circumstance, and triumphing at last.” Oliver does display a strong moral code throughout the duration of the novel and, for the most part, engages in morally questionable/illegal activity only when he is forced into it. However, the scene in which Oliver attacks Noah is a major change in behavior for him, bordering on out of character. What might be construed as an act of deliberate “wicked” behavior on Oliver’s part is truly a moment in which Oliver is pushed too far– but he doesn’t snap until the memory of his late mother is insulted:

“’A regular right-down bad ‘un, Work’us,’ replied Noah, coolly. ‘And it’s a great deal better, Work’us, that she died when she did, or else she’d have been hard labouring in Bridewell, or transported, or hung; which is more likely than either, isn’t it?’

Crimson with fury, Oliver started up; overthrew the chair and table; seized Noah by the throat; shook him, in the violence of his rage, till his teeth chattered in his head…A minute ago, the boy had looked the quiet child, mild, dejected creature that harsh treatment had made him. But his spirit was roused at last; the cruel insult to his dead mother had set his blood on fire.” (pg 52-53)

In this passage, Dicken’s wording– the assertion that harsh treatment had a hand in molding Oliver’s personality, and his description of how “his spirit was roused at last,” for example– imply that Oliver should not be judged harshly for this act due to the fact that it was his environment and the many hardships he was forced through that caused this event to occur. In fact, the way Dickens writes this scene makes it seem almost heroic, as though to suggest that Oliver was in the right to defend the honor of his deceased mother against the cruel attacks of the parish boy. Since Oliver is shown to cherish the memory of his mother, it is understandable that he would lose his typically impeccable moral judgement for the sake of defending her. What he does isn’t necessarily wrong from a moral standpoint, and despite the fact that Oliver attacked another person, it is arguable that Goodness still triumphs over Evil in that Noah was, in a sense, punished for his evil actions.

This passage also suggests that, no matter how good or virtuous people may be, they can only be pushed so far before they resort to “immoral” activity in order to defend themselves or their loved ones. This raises an interesting point about Dickens’ moral views on the lower class; seeing as Dickens wrote Oliver to be an example of Goodness, the fact that even he winds up being pushed to such violent measures under the pressures of lower class life could imply that Dickens disagrees with the commonly held belief of the times that the lower class was simply criminal by nature and thus deserved their lot in life. Through Oliver Twist, Dickens seems to be suggesting that the lower class is associated with criminal behavior because its members were pushed to extreme measures by the cruelty and hardship they faced in their lives, and that any person forced to live like that would wind up being pushed to such immoral extremes eventually.

(Group 6’s reply to Group 4)

Group 4 argues that Oliver Twist was used as a paradigm for how even the most morally good person may be corrupted or pushed too far based on their circumstances; group 4 asserts that Oliver’s “wicked” behavior toward Noah serves to prove this point. While Oliver may have acted harshly, many would argue that neither Oliver nor Noah could be held accountable for their actions. Just as group 4 contends that Dickens’ beliefs on how lower class individuals are simply the products of their environments and not their innate moral degeneracies, both Oliver and Noah are unable to properly settle their differences given their respective upbringings.

While some may claim that Dickens wanted to excuse Oliver for his actions in stating that “his spirit was roused at last,” another possibility is that his spirit should’ve been roused sooner. Dickens may be alluding to the idea that under normal circumstances, any other person would have acted out by then. With the same temperament in mind, Noah would be just as easily excused for his behavior. While Noah isn’t the exemplary hero or morally good “Oliver Twist,” he serves to represent what Oliver could have easily become.

Dickens uses Oliver to demonstrate “the principle of good surviving through every adverse circumstance, and triumphing at last,” but does this equate to Oliver himself being “pure good?” In his preface, Dickens explains how his strategic use of morally devoid characters and situations reveal his own views. He says “I confess I have yet to learn that a lesson of the purest good may not be drawn from the vilest evil.” While some may see Oliver as a force for “the principle of Good,” Oliver does his best to avoid trouble but is far from a traditional heroic character. Oliver is a force for good simply because he reveals evil to a large audience. Oliver does not single-handedly eradicate evil but his indomitable spirit allows him to expose and overcome it. In this sense, Oliver isn’t necessarily infallible and as such isn’t acting out of character when he fights Noah.

On the other hand, Oliver may have been acting heroically in defending his mother’s integrity. It is possible that Oliver is in fact used as a counter-argument to the idea of people who are innate moral degenerates. Oliver may be the opposite: someone who is born infallibly good, an archetypal saint, having innate knowledge of Christian values despite never having learned how to pray. The very absurdity of Oliver’s goodness may even serve to raise doubt in those who believe in infallible moral depravity and notions of how the poor are fixed to their circumstances.

Another case can be made based on Dickens’ wording in his preface statement. He speaks of good “surviving.” Using this wording, Dickens doesn’t claim that goodness must be absolute, but rather something enduring and resilient. A good example of enduring goodness is in *spoilers* Nancy who does a great deal of wrong throughout her life but is nonetheless shown to be quite loyal and selfless. Likewise, Oliver’s good may not be the pinnacle of goodness, but it persistent.

Group 3

In response to the question posed, a particular area of the book that warrants close attention can be found in Chapter XXX, in which Oliver finds himself taken in by the family he attempted to rob. While lying injured in bed, the owners of the home find themselves debating what to do with him, with their responses ranging from disbelief at his involvement to a firm commitment to not turn him over to the police. Specifically, the doctor mentions to Rose that “crime, like death, is not confined to the old and withered alone,” and that the “young and fairest are too often its chosen victims”. Upon seeing that Oliver is at risk of imprisonment for his involvement, Rose thinks that the child must have been forced into this life, having never felt “a mother’s love, or the comfort of a home”, and pleads with her aunt to not send him to prison, “which in any case must be the grave of all chances of amendment.” Here we see a moral dilemma put forward by Dickens: regarding a question of human agency. how responsible is Oliver, and by extension many other criminals of Dickens’ time, for his own illegal actions? In a book that shows in unflinching detail the lives of both the poor and the criminal. to what degree are these characters mere victims of circumstance, rather than agents acting of their own volition? While one might argue that Oliver is ultimately responsible for his own choices and should pay the price for them, it is our view that Dickens’ implied narration of the novel firmly believes in criminals who are forced into crime, and for whom the grave punishments created for unrepentant scoundrels acts more as a trauma than an aid. Given the choice the family makes in caring for Oliver and refusing to turn the boy away, criminal though he was, it is our opinion that the moral stance in the novel is in favor of taking a second look at the urban poor who turn to crime out of desperation rather than malice, and supports turning a judgement eye more to the institutions that bred such despair than the despairing themselves.

In Max Garnaat’s response for Group 3 he concludes, “It is our opinion that the moral stance of the novel is in favor of taking a second look at the urban poor who turn to crime out of desperation rather than malice.” He than defines the second look as, “turning a judgment eye more to the institutions that bred such despair than the despairing themselves.” We agree that Dickens wants a second look at the moral implications of the, “urban poor,” but would like to clarify the “second look” as a second perspective that does not just judge the institutions, but assesses the level of agency a person or institution has in moral decisions.

We would like to focus on the type of agency Dickens depicts that depends on age, that is the more experiences one has the more agency they gain over their actions. Group 3 brings up an excerpt from Chapter XXX that perfectly highlights this concept as they quote, “crime, like death, is not confined to the old and withered alone.” Here Dickens compares crime to the inevitability of death, recognizing that when discussing crime agency is not always guaranteed. Dickens elaborates, “the young are too often its chosen victims.” Here Dickens presents age as an important factor in agency, suggesting that the young have less agency than the old.

Of course there are other examples of how age plays a role in agency, Oliver’s fight with Noah and our perceptions of Fagin’s morals given that he is an autonomous adult, but for the sake of brevity I come to a close.

Response Post written by Kevin O’Connor

Other Group members- Hannah Glase, Mike Stoianoff, Colin Peartree, Michael Adams

In their presentation, Group 2 mentioned that a review by Richard Ford denounced Dickens’ work due to his use of hyperbole. Though Ford accuses Dickens of over-exaggerating his portrayal of the workhouses, our group believes that, rather than conveying a falsehood to his audience, Dickens’ use of exaggeration calls attention to the immoral treatment of the poor in 19th century England, conveying Dickens’ own moral stance on the situation.

An apt example of Dickens’ use of hyperbole is his depiction of Mr. Fang, the police magistrate. “Mr. Fang was a lean, long-backed, stiff-necked, middle-sized man…His face was stern, and much flushed. If he were really not in the habit of drinking rather more than was exactly good for him, he might have brought action against his countenance for libel, and have recovered heavy damages” (Dickens 77). This unappealing description and Dickens’ usage of the name “Fang” clearly convey to the audience Dickens’ disdain for this character. This trend continues throughout chapter XI of Oliver Twist. Mr. Fang is portrayed as overly-aggressive in his speech and mannerisms, speaking “peremptorily” and “contemptuously” to Mr. Brownlow who has done nothing to garner such rudeness. Mr. Fang is also ruthless in his interrogation of Oliver, clearly uncaring about Oliver’s pale face and timid demeanor. “Stuff and nonsense!” said Mr. Fang: “don’t try to make a fool of me” (79). Here, Mr. Fang is exemplifying the perspective of the wealthy at the time. Oliver is feeling ill and does faint, but Mr. Fang does not believe him. Similarly, the wealthy believed that the poor were lazy scoundrels who would use any excuse to receive free care that they wouldn’t have to work for. Dickens uses this scene to demonstrate to his wealthy audience that the poor are not at fault for their situation. They are truly in need of assistance, a responsibility that the wealthy are called on to assume.

In order to further portray the absurdity of Mr. Fang’s actions, Dickens juxtaposes him with Mr. Brownlow, a mild-tempered, elderly gentleman. Contrasting greatly with his depiction of Mr. Fang, Dickens describes Mr. Brownlow with much more reverence and respect in an effort to sway his audience’s opinion in favor of Mr. Brownlow. Whereas, Mr. Fang “growl[s] with very ill grace” (80), Mr. Brownlow is known to speak “respectfully” and “gentlemanly.” His actions also highlight his moral character. “Mr. Brownlow’s indignation was greatly roused; but, reflecting, perhaps that he might only injure the boy by giving vent to it, he suppressed his feelings, and submitted to be sworn at once.” (78) Here, Mr. Brownlow is putting aside his offense at Mr. Fang’s unwarranted abruptness for the sake of Oliver’s safety, demonstrating a fundamental act of morality – putting others before yourself. In addition, Dickens directly calls out those in positions of power through his juxtaposition of Mr. Fang’s “comical effort to look humane” (81) with Mr. Brownlow’s truly humane adoption of Oliver, as exemplified in Chapter XII’s heading, where Oliver is “taken better care of, than he ever was before” (81). No matter how they attempt to spin it, the wealthy have no true defense for the implementation of the workhouses and their harsh treatment of the poor. They acted out of greed, with no regard for human compassion.

A critical reading of this chapter yields Dickens’ moral stance on the workhouses and the poor law. His effective use of characterization and exaggeration allow the readers to see that Dickens favors Mr. Brownlow, depicting him as a moral compass for his audience, and condemns Mr. Fang, a cruel and uncaring individual, thus condemning his wealthy counterparts in 19th century England.

Group 5

Group 1 argues that Dickens successfully employs hyperbole throughout Oliver Twist in order to draw attention to his views regarding the New Poor Law and the immoral treatment of the lower class in 19th century England. While we agree with this statement overall, we disagree with the example that Group 1 uses to make their case. While the description of Mr. Fang’s appearance and mannerisms do imply disdain for this character, it cannot be said that these descriptions show Dickens’ disdain for the entirety of the upper class. It is unlikely that Dickens is using Mr. Fang to reflect his views on the upper class since, as a magistrate, it is more likely that Mr. Fang belongs to the middle class. Furthermore, Mr. Brownlow, who IS a member of the upper class, is said by Group 2 to provide a moral compass for the novel’s audience. This provides a conflict with their argument that Dickens is essentially showing the upper class as an entity of wickedness. The examples Group 1 use can be applied to the situation if their stance is amended so that the issue with the poor law is the procedures and institutions it caused, rather than an issue between upper and lower class.

While the Literary Gazette justifiably praised Dickens for his brutally honest assessment of workhouse conditions and public mentality towards the poor, one must realize that not all of Dickens’ moral interjections are expressed by the author’s voice alone; rather, Dickens often uses his characters’ views and statements as springboards to introduce or expound upon his own views.

During Oliver’s meeting with the Board, the gentlemen berate Oliver for his lack of knowledge and Christian morals. At first, Dickens agrees with the gentlemen, saying that “it would have been very like a Christian, too if Oliver had prayed for the people who fed and took care of him.” However, this concession by Dickens serves only to accent his continuation, “but he hadn’t, because nobody had taught him” (Norton 25). Regardless of the ideally rhetorical situation he created for himself in this scene, Dickens strengthens his argument by positing his defense of the morally uneducated poor between the words of privileged men.

By way of his commentary on Oliver’s lack of Christian education, Dickens also draws attention to the lack of general education among the impoverished. Whereas one of the gentleman tells Oliver, “you have come here to be educated and taught a useful trade,” another member of the board–in apparent agreement–only assures Oliver that he’ll “begin to pick oakum” (Norton 25). The second man’s qualification/removal of the promise of education conveys simply a serious problem with workhouses. As a result of the 1834 Poor Law, it was more likely for a poor child to be working in a workhouse than attending, say, grammar school. Likewise, the Law’s emphasis on the policy of “less eligibility” meant, in part, that a lack of education qualified one to work. Even with the institution of workhouse schools—in which “reading, writing, arithmetic, and the principles of the Christian Religion” were supposed to be taught—the quality of education varied greatly depending on funds and the workhouse board’s belief as to which aspects of education happened to be practical for the workhouse.

http://www.workhouses.org.uk/education/workhouse.shtml

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Less_eligibility

In Group 6’s response to the blog post, they suggest that, through Dickens’ comments on Oliver’s lack of religious education, he intended to highlight the dismal lack of opportunity to receive an education among the lower class. Dickens reveals his opinions on this topic in the passage describing Oliver’s first meeting with the Board, when the gentlemen there are discussing Oliver’s lack of sense. According to Group 6, the author’s views are made apparent when he “agrees with the gentlemen” as they express their doubt about Oliver’s spiritual habits but continues on to state that Oliver had simply never been taught proper Christian behavior, maintaining that his spiritual ignorance is not his fault. Our group, having made a similar argument in our own reply, agrees with this view. We would, however, like to revise one small detail of this argument.

Group 6 claims that Dickens initially agreed with the gentlemen on this matter, but we interpreted that passage a bit differently. Dickens’ wording in that paragraph– and, in particular, his use of italics– gave us the impression that, rather than admitting that the gentlemen’s observations were valid, Dickens was instead employing the use of his signature sarcasm for a more scornful form of disagreement. We believe that the entire point of this passage was to suggest that the gentlemen had no right to look down on or question Oliver’s spirituality due to the fact that it was more the fault of the upper class running the workhouses than that of the residents of those workhouses.

To ascertain a writer’s intentions or moral stance, one must first look at the man and his times, apart from the text, then analyze the story and characters for congruences. In response to the New Poor Law, Dickens positions himself as a champion of the poor and acerbic social critic during a key scene in Chapter Two of Oliver Twist, taking moral stance against the social stratification of Victorian society and treatment of the impoverished. He is not simply reporting the situation as it is, as an anonymous contemporary writes in The Monthly Review, he is saying that the situation is morally wrong, that the system is broken and it needs to change.

In Chapter Two, Oliver asks for more. Through the words and actions of the characters in this scene, we can see Dickens’ sympathy for the poor, his disdain for well-off people unwilling to help, and his judgment of governmental procedure. Dickens’ sarcastic descriptions of the outrage and astonishment that follow Oliver’s request serve to caricaturize and condemn the upper/middle class officials who perpetuate the plight of the poor:

“Child as he was, he was desperate with hunger, and reckless with misery. He rose from the table; and advancing to the master, basin and spoon in hand, said: somewhat alarmed at his own temerity:

‘Please, sir, I want some more.’

The master was a fat, healthy man; but he turned very pale. He gazed in stupified astonishment on the small rebel for some seconds, and then clung for support to the copper. The assistants were paralysed with wonder; the boys with fear…” (Dickens 34).

“Horror was depicted on every countenance.

‘For MORE!’ said Mr. Limbkins. ‘Compose yourself, Bumble, and answer me distinctly. Do I understand that he asked for more, after he had eaten the supper allotted by the dietary?’

‘He did, sir,’ replied Bumble.

‘That boy will be hung,’ said the gentleman in the white waistcoat. ‘I know that boy will be hung.’

Nobody controverted the prophetic gentleman’s opinion. An animated discussion took place. Oliver was ordered into instant confinement.” (Dickens 34).

Dickens draws attention to the obvious, intrinsically wrong, social injustice of a frail, starving boy being refused food from a fat man who has plenty to give. Rather than simply telling it like it is, like The Monthly Review suggests, the hyperbolic descriptions of shock and horror satirize the absurdity and inhumanity of the government’s treatment of poverty, via the New Poor Law.

Furthermore, the anonymity of the unnamed gentleman in the white waistcoat serves to represent the gentry, high society as a whole, and their unjustifiably cruel treatment of the substratum of Victorian society. Born into poverty and disadvantage, without parents, Oliver is continuously punished for being born. Dickens uses the meaningless, senseless suffering of a child to expose the problems inherent in Victorian society, to provide the impetus for social change, and to show that something more needs to be done: “Nobody controverted the prophetic gentleman’s opinion.”

Group 3 Response

Group 2 points to the pitiful scene of Oliver asking for more as a reflection of Dickens’ pity for the poor and anger for those members of the upper class who have helped to subjugate them. We agree that Dickens uses satire and hyperbole in order to draw the readers’ attention to the plight of the lower classes that was mostly ignored by the influential part of society. Additionally, Dickens uses satire in order to appeal to the upper classes. The use of high brow humor that only the wealthy and educated could understand is a calculated move by Dickens in order to attract the attention of those whose power he is trying to target.